Alluring Myths or Real-Life Conservation Crisis:

Is There Still Hope for the Sperm Whale?

By: Autumn Homer, Shark Team One

An elusive creature, spending less than 20% of its life at the ocean's surface, the sperm whale has captivated the minds of people all over the world for centuries. Herman Melville’s classic tale, about the hunt for an aggressive white sperm whale who had dismembered the limbs of multiple captains, has been immortalized into a legend of fear and distrust of these animals. Moby Dick, was based on of a real albino whale who supposedly killed 30 men in the 1800s. (1.) Whether this was an old sailors’ tale or not, these stories have grown into a lasting reputation of these deep sea creatures. But are these rumors true? Their mammoth size, mysterious life under the sea and troublesome relationship with sailors generated the perfect concoction for a horror story, but today research is being done to push past the myths and discover the truth about these giants.

To put the origin of these sailors’ stories into perspective, they took place during the commercial whaling era in the 1800s to mid 1900s. During the peak of this time, around the 1950s, about 25,000 whales were killed per year, dramatically depleting the global population. These whales were highly sought out and massacred in search of a substance that had the value similar to oil of its time. Their large heads are filled with a white, waxy substance called spermaceti. Meaning “seed of the whale”, due to the fact that it was mistakenly thought to be seminal fluid. This substance was highly valuable as it was rated at a much higher quality than the oil found in the blubber of other whales, and it could be used for a variety of things. Lamps, soaps, cosmetics, dog food, brake fluid, cattle fodder, leather preservers, vitamin supplements and butter were all products that benefited from this substance. The industrial revolution was heavily tied with commercial whaling, as the oil fueled the new industry. (2.)

Along with the practical use of spermaceti there was also a cultural identity that formed among the people who harvested this substance. Hal Whitehead, a biologist at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia said, “Old-time whaling had a dual identity. It was a way of getting stuff we needed, but also a wild, romantic chase.” This dangerous romanticism, paired with a highly valuable commodity led to a massive reduction in the sperm whales' population. Due to the large decrease, the International Whaling Commission put a ban on whaling. Before commercial whaling, scientists estimate that there were more than one million sperm whales. Today that number may be around 360,000, although it is unknown whether the populations are increasing. (3.)

While commercial whaling was detrimental to the species population health, it is also where most of our knowledge of the species came from. Whaling gave us access to an otherwise remote animal and sparked an interest in something that was virtually unknown. Today, scientists like Whitehead study sperm whale communication strategies in an effort to understand how they socialize and hunt for food to hopefully find ways to help the remaining populations. Like other whale species, the sperm whale uses echolocation to hunt for their food. Unlike whales such as the humpback whose vocalizations sound like a song, the sperm whale is known for its loud knocking. Whalers in the 1800s used to nickname them “the carpenter fish”, because they would hear what sounded like a hammering on the ship’s hull.

To put the origin of these sailors’ stories into perspective, they took place during the commercial whaling era in the 1800s to mid 1900s. During the peak of this time, around the 1950s, about 25,000 whales were killed per year, dramatically depleting the global population. These whales were highly sought out and massacred in search of a substance that had the value similar to oil of its time. Their large heads are filled with a white, waxy substance called spermaceti. Meaning “seed of the whale”, due to the fact that it was mistakenly thought to be seminal fluid. This substance was highly valuable as it was rated at a much higher quality than the oil found in the blubber of other whales, and it could be used for a variety of things. Lamps, soaps, cosmetics, dog food, brake fluid, cattle fodder, leather preservers, vitamin supplements and butter were all products that benefited from this substance. The industrial revolution was heavily tied with commercial whaling, as the oil fueled the new industry. (2.)

Along with the practical use of spermaceti there was also a cultural identity that formed among the people who harvested this substance. Hal Whitehead, a biologist at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia said, “Old-time whaling had a dual identity. It was a way of getting stuff we needed, but also a wild, romantic chase.” This dangerous romanticism, paired with a highly valuable commodity led to a massive reduction in the sperm whales' population. Due to the large decrease, the International Whaling Commission put a ban on whaling. Before commercial whaling, scientists estimate that there were more than one million sperm whales. Today that number may be around 360,000, although it is unknown whether the populations are increasing. (3.)

While commercial whaling was detrimental to the species population health, it is also where most of our knowledge of the species came from. Whaling gave us access to an otherwise remote animal and sparked an interest in something that was virtually unknown. Today, scientists like Whitehead study sperm whale communication strategies in an effort to understand how they socialize and hunt for food to hopefully find ways to help the remaining populations. Like other whale species, the sperm whale uses echolocation to hunt for their food. Unlike whales such as the humpback whose vocalizations sound like a song, the sperm whale is known for its loud knocking. Whalers in the 1800s used to nickname them “the carpenter fish”, because they would hear what sounded like a hammering on the ship’s hull.

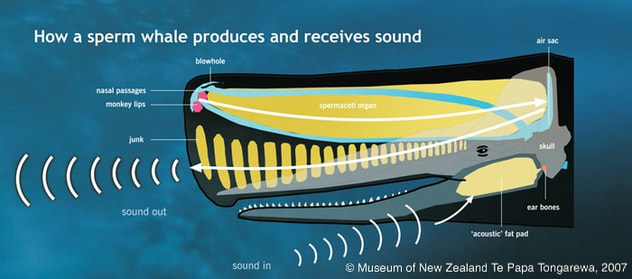

These sounds are created through a complex system that takes place inside the giant head of the whale. The animals are able to emit pulses of sound in particular patterns. It is even thought that they can aim their clicks at certain targets in search of prey. The way it works is through the whale’s spermaceti organ (the valuable substance whalers sought) and a large chunk of oil-saturated fatty tissue called “the junk”. Surrounding these, are two long

nasal passages. The left nasal passage runs directly to the blowhole which lies at the top of the whale’s head. The right nasal passage does not have a straight path, its twists and turns form air-filled sacs that are able to reflect sound. Near the blowhole is a pair of clappers called “monkey lips”. To make a sound, the whale will force air through its right nasal passage to the monkey lips, which then shut. This creates a click noise which bounces off the air filled sacs, through the junk and out into the water. It is thought that the whales might have the ability to change the shape of the spermaceti organ and the junk, which would allow them to aim where they send the clicks. (4.)

These noises are how the whales are able to socialize with one another and some scientists have even hypothesized that with certain clans of whales there are particular vocalizations that are unique identifiers, essentially names. Their complex language and social dynamic is intriguing. Having the largest brain of any creature to live on earth, their intelligence is something we still don’t fully understand. (5.) It is some scientists’ belief that the whales have a good memory. Due to the social groupings and lifelong companions these animals have throughout their lifespan, it is assumed they have to be able to remember them all. Their cerebral cortex, which is the part of the brain responsible for thinking, perceiving, and producing and understanding language, is also much more elaborate than a human cortex, which implies it is a complex function.

It is this good memory that some think the stories of Moby Dick may have originated from. If the whales themselves remembered the whalers’ ships who had attacked them, is it possible they sought to attack back? The Essex, a ship that sunk in 1820 because it was rammed by a sperm whale was what sparked Melville’s imagination to write his classic tale. Dr. Lindy Weilgart, a research associate in the department of biology at Dalhousie University in Canada states, “I do believe a sperm whale is capable of the aggression necessary to attack a ship, especially a mother if her young is threatened.” Whalers during this time were known to first harpoon calves, then keep them alive to attract the rest of the pod who would come assist the baby. They would then kill the adults. A cruel method of hunting, that demonstrates the strong social bonds these whales have for one another. (6.) Essentially, these whales may not seek out ships to attack, but when a relative is in danger, aggression is possible.

nasal passages. The left nasal passage runs directly to the blowhole which lies at the top of the whale’s head. The right nasal passage does not have a straight path, its twists and turns form air-filled sacs that are able to reflect sound. Near the blowhole is a pair of clappers called “monkey lips”. To make a sound, the whale will force air through its right nasal passage to the monkey lips, which then shut. This creates a click noise which bounces off the air filled sacs, through the junk and out into the water. It is thought that the whales might have the ability to change the shape of the spermaceti organ and the junk, which would allow them to aim where they send the clicks. (4.)

These noises are how the whales are able to socialize with one another and some scientists have even hypothesized that with certain clans of whales there are particular vocalizations that are unique identifiers, essentially names. Their complex language and social dynamic is intriguing. Having the largest brain of any creature to live on earth, their intelligence is something we still don’t fully understand. (5.) It is some scientists’ belief that the whales have a good memory. Due to the social groupings and lifelong companions these animals have throughout their lifespan, it is assumed they have to be able to remember them all. Their cerebral cortex, which is the part of the brain responsible for thinking, perceiving, and producing and understanding language, is also much more elaborate than a human cortex, which implies it is a complex function.

It is this good memory that some think the stories of Moby Dick may have originated from. If the whales themselves remembered the whalers’ ships who had attacked them, is it possible they sought to attack back? The Essex, a ship that sunk in 1820 because it was rammed by a sperm whale was what sparked Melville’s imagination to write his classic tale. Dr. Lindy Weilgart, a research associate in the department of biology at Dalhousie University in Canada states, “I do believe a sperm whale is capable of the aggression necessary to attack a ship, especially a mother if her young is threatened.” Whalers during this time were known to first harpoon calves, then keep them alive to attract the rest of the pod who would come assist the baby. They would then kill the adults. A cruel method of hunting, that demonstrates the strong social bonds these whales have for one another. (6.) Essentially, these whales may not seek out ships to attack, but when a relative is in danger, aggression is possible.

Their remarkable intelligence and complex social structure are only a couple reasons why we need to protect these animals. Sperm whales can be found in virtually all marine environments deeper than 1,000 meters that are not covered by ice. Despite this large habitat range, there are anthropogenic threats that reach them all over the world. This includes whaling. Not just a romantic notion of the past, some countries such as Japan, still hunt these whales, despite their conservation status, which is listed as vulnerable by the IUCN. Another major issue is ship strikes. Particularly in the Caribbean where there are high levels of marine traffic surrounding the islands due to imports of goods. There have been multiple reported sperm whale deaths in the Canary Islands, where routes for high-speed ferries, cruise ships, and other boats are common in prime sperm whale habitat.

Pollution is another large threat to sperm whales. From noise pollution which disrupts their communication to chemical pollutants that contaminate the water and physical pollution that they accidentally ingest, the ocean is now filled with dangerous hazards. In 2016, 13 sperm whales were found washed up near the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. That year, more than 30 sperm whales had been found washed up in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, France, Denmark and Germany. After a thorough necropsy, researchers found a 43 foot long shrimp fishing net, a plastic car engine cover, and large amounts of plastic. When whales are unable to digest the trash, it sometimes causes them to feel full, which reduces their instinct to feed and eventually leads to malnutrition and death. (7.)

While populations are low for these reasons, there are management plans in place. Although these plans definitely have room for development. The International Whaling Commission manages sperm whale populations under the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling and the Schedule of the Convention lists sperm whale seasons along with size and catch limits. One of the biggest flaws with these regulations is, although catch limits are currently set at zero, not every country is a member of the International Whaling Commission. This means the same rules may not apply to everyone, and a lot of work can be done to improve these regulations. (8.) Sperm whales currently have sanctuaries in the Indian and Southern Oceans around Antarctica. (9.)

So is the legend of a monster whale true? Maybe to a squid, but for us they are another animal whose populations are greatly suffering due to human impact. There is still so much to learn about these giants. History shows a gruesome discovery for the study of these creatures, but today less invasive tactics are used. From photo identification of specific populations, to audio recordings of vocalizations, to citizen science conservation expeditions, there is still hope for the sperm whale. While the myths of dangerous sea creatures can be alluring stories, the real danger today lies in the health of our oceans and we must do what we can to keep the creatures in it from becoming myths themselves.

Pollution is another large threat to sperm whales. From noise pollution which disrupts their communication to chemical pollutants that contaminate the water and physical pollution that they accidentally ingest, the ocean is now filled with dangerous hazards. In 2016, 13 sperm whales were found washed up near the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. That year, more than 30 sperm whales had been found washed up in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, France, Denmark and Germany. After a thorough necropsy, researchers found a 43 foot long shrimp fishing net, a plastic car engine cover, and large amounts of plastic. When whales are unable to digest the trash, it sometimes causes them to feel full, which reduces their instinct to feed and eventually leads to malnutrition and death. (7.)

While populations are low for these reasons, there are management plans in place. Although these plans definitely have room for development. The International Whaling Commission manages sperm whale populations under the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling and the Schedule of the Convention lists sperm whale seasons along with size and catch limits. One of the biggest flaws with these regulations is, although catch limits are currently set at zero, not every country is a member of the International Whaling Commission. This means the same rules may not apply to everyone, and a lot of work can be done to improve these regulations. (8.) Sperm whales currently have sanctuaries in the Indian and Southern Oceans around Antarctica. (9.)

So is the legend of a monster whale true? Maybe to a squid, but for us they are another animal whose populations are greatly suffering due to human impact. There is still so much to learn about these giants. History shows a gruesome discovery for the study of these creatures, but today less invasive tactics are used. From photo identification of specific populations, to audio recordings of vocalizations, to citizen science conservation expeditions, there is still hope for the sperm whale. While the myths of dangerous sea creatures can be alluring stories, the real danger today lies in the health of our oceans and we must do what we can to keep the creatures in it from becoming myths themselves.

About the author: Autumn Homer is a recent graduate from Stetson University, where she majored in Environmental Studies and Communications with a minor in psychology. She has always had a passion for animals and you can find her volunteering at one rescue organization or another. She currently works at Loggerhead Marinelife Center and spends her spare time reading, writing, or out on the water. Autumn volunteers for Shark Team One and is one of our conservation and ecology writers!

1. Than, K. (2011, February 11) "Rare 1823 Wreck Found-Capt. Linked to “Moby Dick,” Cannibalism" https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2011/02/110211-two-brothers-whaling-ship-pollard-science-nantucket-noaa

2. Wagner, E. (2011, December) "The Sperm Whale's Deadly Call" https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-sperm-whales-deadly-call-94653

3. Gero S, Whitehead H (2016) Critical Decline of the Eastern Caribbean Sperm Whale Population. PLoS ONE 11(10): e0162019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162019

4. Wagner, "The Sperm Whale's Deadly Call"

5. "Sperm Whale" https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/s/sperm-whale

6. Coxon, R. (2013, December 20) "The real Moby Dick: Do whales really attack humans?" https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-25430996

7. Malik, W. (2016, March 31) "Sperm Whales Found full of Car Parts and Plastics" https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/03/160331-car-parts-plastics-dead-whales-germany-animals

8. Gero S, Whitehead H, Critical Decline of the Eastern Caribbean Sperm Whale Population

9. "International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling, 1946 Schedule, amended 2016"

Sperm whale photo credits: © Angela Smith, 2018 • Illustration credit: © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, 2007 • Video credits: © Angela Smith and Shark Team One • All sperm whale images and video created under Dominica Government Research Permit 23/11.

2. Wagner, E. (2011, December) "The Sperm Whale's Deadly Call" https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-sperm-whales-deadly-call-94653

3. Gero S, Whitehead H (2016) Critical Decline of the Eastern Caribbean Sperm Whale Population. PLoS ONE 11(10): e0162019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162019

4. Wagner, "The Sperm Whale's Deadly Call"

5. "Sperm Whale" https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/s/sperm-whale

6. Coxon, R. (2013, December 20) "The real Moby Dick: Do whales really attack humans?" https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-25430996

7. Malik, W. (2016, March 31) "Sperm Whales Found full of Car Parts and Plastics" https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/03/160331-car-parts-plastics-dead-whales-germany-animals

8. Gero S, Whitehead H, Critical Decline of the Eastern Caribbean Sperm Whale Population

9. "International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling, 1946 Schedule, amended 2016"

Sperm whale photo credits: © Angela Smith, 2018 • Illustration credit: © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, 2007 • Video credits: © Angela Smith and Shark Team One • All sperm whale images and video created under Dominica Government Research Permit 23/11.